I grew up with some awareness of the works of industrialist and women’s advocate Esther Ocloo in my life, most of it after her death in 2002. One of Esther Ocloo’s daughters was a neighbour and her Nkulenu products were well within reach. I have a particular fondness for Nkulenu’s orange squash, which was a trusty companion during my time in boarding school. But I can’t say I would have ever heard of one of the more underrated Ghanaians if I grew up elsewhere.

I took a small friends and family poll because of this sentiment, fearing that indeed the average Ghanaian had no idea who Esther Ocloo was. I was not surprised at the “whos” and “oh okays” that met my small enquiry. Granted, this was not the most rigorous research method, but it paints at least a rough stick figure portrait of a society that is embarrassingly unaware of a major cornerstone ready to be harnessed in pursuit of the development that has eluded our grasp for decades.

Esther Ocloo worked her way up from a foundation of 10 shillings to 12 jars of marmalade and then over the next few decades, went on to become one of Ghana’s leading entrepreneurs. She didn’t stop there; she also became an exponent of the role of women in economic development. I only grasped the overall extent of her impact the day Google honoured her with a doodle in 2017. That led me down a rabbit hole of articles that paid her tribute and chronicled her achievements.

When I think about the shelving of Esther Ocloo in the public consciousness I am reminded of the absence of her name from any discourse during my about-three years taking history in secondary school. It’s a bit of crime that one could pass through school and not know her name, along with other Ghanaians that could be positioned as beacons of inspiration for a country still wandering in search of an identity.

This speaks to a grave dysfunction encapsulated in the fact that debate over curriculum in schools was recently reduced to partisanship with the back and forth between Nkrumahists and persons flying the flag of the Danquah tradition. Their legacies are undoubtedly safe and their contributions to our independence will never be overstated. That said, maybe there are more merits in centring figures that left a mark, even if on a micro scale.

The importance of women like Esther Ocloo is at least not lost on the likes of Kofi Otutu Adu Larbi. In his book ‘They Touched Us For Good’, he reflects on the seeds of hope people like her sowed as they strove for the best possible version of themselves, versions that revolved around service to society.

As he put it to me, he is “on a crusade to bring out the good” women like Esther Ocloo have contributed to not only Ghana but the world. In his view, “the women have been more influential” to building Ghanaian society, though he adds that “they have been on the quiet.”

“That is why we need to celebrate them for us to see what it is they are made of so we can learn from them,” he insisted.

There is a conversation to be had about how we have deployed (or rather failed to deploy) history as an anchor for developing a sense of identity as a nation and fuelling development. History is much more than a pathway for posterity. It is the foundation of our eventual destination; integral to understanding a people’s conception of themselves.

Esther Ocloo’s ilk could form the glue that holds a web and tissue of a new movement together, at least on a micro scale. Finding the ground zero of any culture may be difficult but there are individual cornerstones that are effective markers for sections of the society to build on. But no building can take place without the proper context – a context which can only probably be provided in schools hence my worry with the lack of depth and vision in the school curriculum in this regard. We may not need reminding of this fact, but education should not just be concerned with the nuts and bolts of teaching but also molding the agency of a person and by extension a society through experiences.

The list of forgotten women in Africa across various spheres in society may take donkey years to compile. Even those, like Esther Ocloo, who have tangible totems to remind us of their legacy rarely get the same amount of praise as male leaders. Think about what it would mean if a lot of these sidelined characters got the fabled treatment of, say, a Yaa Asantewaa, who remains an icon of resistance. As a child, the mention of her name conjured up a Joan of Arc type warrior, anchoring the vanguard, leading a charge against the colonisers.

Esther Ocloo didn’t lead armies into battle. But she fought for her own form of liberation; the economic liberation of women. She was the first chairwoman of Women’s World Banking and is noted as one of the pioneers of microlending and the financing of mostly women-run small businesses. Given her background, she believed in the power of small beginnings which is why the businesses were supported with very small loans. Larger loans were made available if the business proved successful.

This idea was sown at the 1975 Mexico City conference that heralded the United Nations Decade for Women. Esther Ocloo became more acquainted with the struggle of women elsewhere; all who would benefit from Women’s World Banking. It was a simple equation for her; education and health care for women in the third world was great but what they needed more than anything was more money in their purse. They and several allies founded Women’s World Banking in 1979 with Ms. Ocloo as chairwoman.

The New York Times has a quote for a speech Esther Ocloo gave in 1990:

”Women must know that the strongest power in the world is economic power. You cannot go and be begging to your husband for every little thing, but at the moment, that’s what the majority of our women do.”

There are some embers of her legacy that still burn, albeit not as strong enough as they should. I was at her 100th anniversary memorial service at Achimota School, her alma mater, where it was heartening to see a crop of youngsters learn about the late Peki native. Hopefully, we will be hearing much more about her as the government looks to get involved in her centenary celebrations as the year progresses.

She was born Esther Afua Nkulenu at Peki-Dzake in the Volta region on April 18, 1919. She rode on a Cadbury scholarship to Achimota School in 1936 despite her parents being poor farmers. After secondary school her prospects were dim. She had no job and was living off relatives. It was at this point the foundational 10 shillings came her way. But the way it came to her left more of an indelible mark.

Her aunt Josephine shelved her own desires to support her through school and the 10 shillings was mere pocket money. But that money was channelled into sugar, firewood, oranges and 12 jars. Esther Ocloo had learned how to prepare marmalade jam in her home science class and she put those skills to the test. She eventually filled all 12 jars with marmalade which she sold for a shilling a jar around government offices. She made a profit in the end.

What followed were contracts to supply her former school and then the military; the latter for which she got a bank loan that birthed the Nkulenu Industries we know today. After six years, she had saved enough money to travel to the UK to study food technology, preservation, nutrition and agriculture.

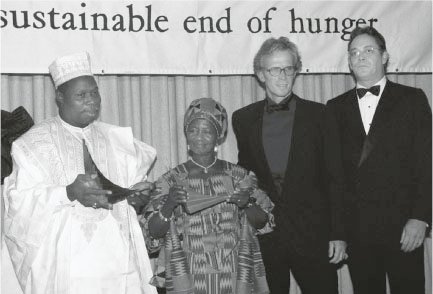

When she returned from the UK, she devoted more time to bettering the economic situation of women; all while she still run her company. She established a programme on a farm to train women in agriculture, food technology as well as in handicrafts. She funded this programme partially with her half of the 1990 Africa Prize. She split $100,000 with Olusegun Obasanjo, the former president of Nigeria. It was an honour bestowed by the Hunger Project for their initiative in working to end hunger in Africa.

There is much more to garner from Esther Ocloo’s life as Otutu Adu Larbi notes in his book ‘They Touched Us For Good.’

“We have built on her in a sense,” he said. “She founded Women’s World Banking. She was a pioneering person who did work on the Association of Ghana Industries so in that sense, we built on her but obviously, there is so much more we can learn from her.”

That some of these women are sidelined in history is a source of frustration for Otutu Adu Larbi. It really isn’t about forgetting about such persons. It is merely a lack of regard for certain historical details, he surmised.

“We don’t forget. I think we just don’t pay attention to details. We don’t pay attention to things in this country. It is about time we started paying attention to the little things; to details that will make a difference in our lives.”

I leave the last word for Otutu Adu Larbi who couldn’t stress enough that we must start looking closer at some of these cornerstones to “see what we can learn from them and see what we can build on them.”

“If we start doing that deliberately as a people and as a nation, I think we will get somewhere.”

Source: Delali Adogla-Bessa, 2019

Leave a Reply